You Don’t Always Know Why, with Kathy Fernandez Blunt

Kathy Fernandez Blunt (Kathy) knows how to live life. At 89 years young, she’s a beloved regular at Myrtle who loves to shares stories about her years as an Emmy-nominated news producer, touring tennis player, mother, and of travels around the world. We spoke with her at her home, just down the street in East Providence.

Above: Photo of Kathy on a trip to Bermuda

Kathy Fernandez Blunt (Kathy) knows how to live life. She’s a beloved regular at Myrtle who loves to share stories about her years as an Emmy-nominated news producer, touring tennis player, mother, and of travels around the world. Born in North Carolina, Kathy spent her teen years in NYC before following love to East Providence. Once in the Ocean State, she studied at Bryant and Brown, taking up admin jobs at school and Trinity Rep. Kathy’s a naturally curious “in the mix” type person; that energy got her looped in with WSBE-TV as a producer and panelist for a public affairs show which in turn, lead to further education at the Northeast School of Broadcasting in Boston. During that same period she’d started a gig at WJAR Radio (NBC), proved her chops, and became the first Black woman there to hold the position of Weekend News Reporter.

Family connections then brought Kathy to D.C. where she served as host, producer, and writer for a number of critically acclaimed programs including Eye on Washington (WDCA) and Black Reflections. In addition, Kathy’s found time to raise a family, own multiple video rental stores, support organizations like Black Miss America and the United Negro College Fund, and sneak in a little mountain climbing, too. We recently visited Kathy’s home in East Providence, turned a recorder on, and asked her to share whatever she felt like sharing. What follows are excerpts from that conversation, edited down for this format. Kathy’s currently at work on her full life story.

The Well (TW): Kathy where do you want to sit?

Kathy Fernandez Blunt (Kathy): I'm cooking a Portuguese meal, Cachupa. It’s like the Cape Verdean Munchupa. Would you like a glass of wine or something?

TW: Yeah, sure. Sure, thank you.

Kathy: You saw the pictures of my daughter, Pam? She looks very much like her mama, I mean her daddy. [Showing photos] This is my husband at a play at Trinity Rep. It was a Shakespearean play. You know I started in Trinity?

TW: Tell me about that.

Kathy: Well first I was a file clerk at Admiral TV. Somebody told me to check out Brown—it was Christine Hathaway, who was Secretary to the Librarian—she told me to take a couple of courses there at night and blah, blah, blah. Someone spotted me somewhere and whatever I was doing, they thought I should go to Trinity. This is when they were in the Trinity Church. I started out as an assistant. What do you call it?

TW: A stage manager?

Kathy: No, no. It was…Executive Assistant. I was also in charge at times...at night, you know when the play is playing. Adrian Hall was the artistic director, and he wanted to know if I wanted to be his and Marion Simon’s assistant. I knew all the actors. So when we went to Edinburgh, I had to get all their birth certificates so I could get them their passports. I don't know if you remember the actor Richard Kneeland? He said, “Kathy, if you tell my age, I’ll have to kill you.” Everybody wanted to play young roles. I said, “Richard, please, I've kept all the secrets.”

TW: Where are you at in life right now? There’s a lot of boxes around here.

Kathy: Well, I'm very befuddled. Is that a word, still? Yeah, my grandma used to use that word. [Someday] this house will be sold. I have my name in at a couple of really nice senior living places. I have property in North Carolina but I don't want to move there. I’ve been away from there since I was 12; I had moved to NYC after my mother passed.

Above: Kathy getting reading to head out to work at WJAR in 1973

TW: So, just no connection there anymore.

Kathy: Yes, all my doctors and other people are in Rhode Island. I go to visit but wouldn’t want to stay. You know, my niece was killed in the World Trade Center and she was a wonderful, gorgeous child who was living with my brother in both NYC and North Carolina.

TW: On 9/11?

Kathy: Second building. I was at the foot doctors when the first [plane] hit Building One. Everybody was like, “What?” They were telling the people in Building Two, which was where my niece was, “Oh, stay put, it's an accident.” Well, then they said, “You've got to get out,” but it was too late. They couldn't use the elevator and they all burned up. I was living in Maryland at the time and I went to be with my brother in Brooklyn, which is where they all lived, and we had to go and bring identification and stuff. Ten years later they found her torso and they shipped it to our home at our church in North Carolina. So I mean, I don't want to go back there. I love it there when I visit, but I don't think I can live there.

[A beeping sound is heard from the kitchen]

Kathy: That's my pot. I don't wanna burn it... We have to cook it in different parts, because you've got pig feet, which are very tough to cook, so you cook that all by itself. And then we've got spare ribs and and then it's beans, all kinds of different beans and kale.

TW: How long have you been in this house? And how’d you end up here?

Kathy: Well, I only lived in this house since 2003. [Years before,] I met a guy in New York and we got married, and so I had to come up to East Providence, which was like…I couldn't just like, walk down the street and go to Broadway anymore. I couldn’t just take a bus or you know, but I got used to it. He’s Spanish and Native, but had been adopted by a Cape Verdean family. My grandmother’s Native, too. So anyway, he passed away and that's a long story. I remarried about five years later. I had bought a house on Lancaster Street in Providence. Do you know Lancaster Street? Yeah, Raymond Patriarca.

Above: Kathy at WDCA in Washtington, DC.

TW: The mob boss?

Kathy: Nice man, my height. Had a black poodle. When he walked the dog there was a goon on each end of the street just in case somebody wanted to pop. I did the story when I was at WJAR.

TW: You did a story when he died, or something else?

Kathy: When Bobo Marrapese supposedly killed Dickie Callei. The story was that Raymond had it done by Bobo when Raymond was away in jail, but there was never any proof of it. You know that scene in the Godfather, in the restaurant?

TW: I’ve actually never seen The Godfather.

Kathy: That's a scene that they supposedly stole from us. One version of the story was that in Johnston, Bobo and Raymond had told everybody to go to the restaurant. That was when the telephones were around from the bar. They were all sitting there drinking and the bartender said, “Dickie, you have a phone call.” So Dickie gets up, goes around the corner and a couple of guys went with him to the phone...when the guys were all gone Dickie was there with 37 stab wounds or something crazy like that. I'm working on this story, I'm new! I’d just graduated from Northeast School of Broadcasting.

TW: How did it get assigned to you? It feels like an intense gig.

Kathy: I had never covered anything like this. The station said, “Kathy, you've got to go.” Knowing what had happened and being new to the industry, it was very intimidating. So my first, my first real gig for TV, yeah. I was the Weekend Reporter.

I had to talk to the cops. The police called and told us where the killers had dumped Callie's body, it was in the Rehoboth area. The police took the body to the morgue, whatever the cops did. I was asking my bosses, “Well, what are we going to do? Take pictures of it?” He said, “Yeah, because you're going to see blood everywhere.” So I said, “Ooh, this is exciting.” It was during the time when we had one color camera and one black and white, and if you wanted to see red blood...use the color camera! The cameraman was a sweetheart. So we were going. A cop said “It's down there, it's a one-way road on the left-hand side.”

Above: Kathy’s press pass from the mid 1970s.

TW: This is not sounding particularly safe.

Kathy: It's one way in and one way out. We're driving along and I'm like, “Oh, my god, we're not alone.” We see this car following us, a yellow Volkswagen, unmarked, and we have the WJAR News Watch 10 logo on our car...everybody knew who we were. So I'm thinking, and the car is coming behind us, and I said to my driver, “You know, I think we should just pull over and let them get ahead of us. Either that or they're going to kill us.” They pulled up next to us and it turned out they were from the Taunton Gazette.

TW: They scooped you on the story?

Kathy: I don’t know, since they were from a different station. But they’d gone ahead and said they couldn't find it. We drove maybe a quarter of a mile further and there it was. We got out and took pictures and it looked to me, it looked like they buried him in his car. I mean, this was a huge spot that they put him in. So we got back and we did the story and you know, I couldn't tell all that. I just said, “Blah, blah, blah...the police called and said yada, yada had been killed.” There was no clue that it was Raymond Patriarca doing until later—I knew some of the gangsters; I was all over Federal Hill so I knew everybody there.

TW: You knew them through reporting or socially.

Kathy: Socially, yeah. Mostly reporting, though, and the thing about it...on the news, you only got a minute and a half tops. Most of the time it's a half, but this was a minute. I managed to get through it and I ended with you know, “Call the police,” and I gave the police number if you want to know more.

Above: Kathy at the Washington Emmy Awards

TW: I think I have this right, you were the first Black female news reporter at WJAR?

Kathy: They had a couple of Black people working as photographers. I forget, but yeah. I'm in contact with them now—they just had their 75th anniversary about four months ago and they omitted me. I have a lot of pictures, but the people there now, I think the only one that's there now that was there during my time is Barbara Morse Silva. The guy that has a Sunday show said to me, “Kathy, you need to call her,” so I called, and she hasn't called me back. It's been four months. I don't want anything, but I want to know why they left me out.

TW: It's a fairly important distinction.

Kathy: Yeah, absolutely, and you'd think they would be proud of having the first woman of color as a local news reporter.

TW: Well, maybe someone will read this and reach out! What are some other memorable stories that you covered?

Kathy: Okay, we got a call from the police, who said a woman had been murdered by her husband in front of the Kentucky Fried Chicken in Johnston. So the news desk said, “Kathy, you're going to have to go to Kentucky Fried and interview the people there, because somebody was murdered.”

So I got there and I saw Donald, my friend who owned it, and he felt really bad. He said the couple had separated—the husband and wife, and he didn't want to let her go. She worked there and he drove up in the parking lot...as she was getting out the door, her husband went over and said, “Come with me,” and this is what they all told me. She said no, so he put her in the car, drove about a quarter of a mile.

I got all these pictures, beautiful pictures from Kentucky Fried. He shot her first, in the car, and then he shot himself. His car veered off the road into somebody's property with trees. When I got there, the cops came over and said “You don't want to take any pictures of the interior of that car,” and I was like, “Why?” He said we could go up there and take pictures outside the car, but nothing inside, out of respect for her, and him too I guess. That was pretty sad. I mean, the Bobo story was scary, but this was sad. To know that could happen to somebody.

TW: I would describe you as an upbeat person, and I'm curious how you compartmentalize seeing things like that—does it get to you?

Kathy: I'm not sure. It was very sad, and the policeman told me not to look inside. But you know, here I am being a nosy new reporter, whatever. I wished I hadn't, but it's in my mind. Compartmentalizing something like that, I don't know how I did it—just being a new reporter and getting out of broadcasting school...trying to show that I learned something and putting it in the right place. The who, what, when, where, whatever. You don't always know why.

Above: Kathy’s graduation photo, Washington Irving High School, NYC, 1954.

TW: What your overall sense of Rhode Island was during your time as a reporter. Like a big picture understanding of the state, maybe?

Kathy: Yeah. Well, my brother had come up from New York to visit and he said, “Oh wow, look at this little place. I saw a sign that said Welcome to Rhode Island and a block later it said Come Back Again! God, he was so funny! But my feelings...I just had no intention of doing anything except maybe getting a job, because my daughter was born when....Oh, okay, before. That was when I did the Emmett Till story. [content warning: graphic images of violence].

TW: Actually let’s maybe switch and follow that—you started talking about it the first time we met.

Kathy: Emmett was killed in 1955. We, I mean, my husband was Roland Fernandez, we were traveling from New York all across the country selling magazines like Look, Life, and Readers’ Digest. We’d been to New Orleans during Mardi Gras and there was a famous restaurant at the time called Buster Holmes in New Orleans that said they had the best ribs in the South.

TW: I think every place in the South makes that claim.

Kathy: It's true! I make my own barbecue sauce. I learned from my grandpa. So we were doing this in 1956 and got to Money, Mississippi. And so my husband, a big tall white guy and me, a cute little brown girl or whatever, had to stop in Money, Mississippi, which we didn't know, we just were stopping along the way. We stayed in every white hotel because they couldn't turn down this white man. [The staff would think] “She looks like she could be Puerto Rican, or Mexican. At least she's not a nigger.”

So we stopped to get a Coke or something and walked in the door and we just looked around, there's nobody there except two guys against the wall on the right, and then the guy behind the counter. And so he looked at us, like I guess they never saw a biracial couple before. We went up to the counter and the guys were still staring, these two guys. The reason we went there is because the sign said “Bryant Convenience” and well, Bryant is my family name.

Now, we didn't have a camera, we never took pictures of anything. I would be filthy rich if I had done that. Whatever. So the guy at the counter said, “I'm going to wait on you kids, but you've got to leave as soon as you can,” and my husband's like, “Why? This is America.” And he says, “See those two guys against the wall? That's Roy Bryant and his brother.” We knew about Emmett Till, how he had been killed by them.

TW: They were just hanging out?

Kathy: Did they ever serve any time in jail? I don't think they served any time. Bryan’ts wife had told her husband that these young black boys—I'm sure she said the N-word—came into the store and they were flirting with her. That's what she told her husband. And her husband got furious. So they went a couple of days later into this boy's Uncle Moses' house. He was visiting from Chicago. So Mr. Roy and his brother knocked on Uncle Moses' door and said, “Where's the boy from Chicago? We need him.” This is what was reported to us later by the person that was there. They pushed Uncle Moses out of the way, went and grabbed Emmett out of bed, broke every bone in his body and dropped him into the Tallahatchie River or whatever it is down there in Mississippi. Later when the undertaker was going to seal the casket his mother said, “Oh, no, no, no, no, no! Leave my boy just the way he is. I want the world to see this.” They had a picture of him in the casket in Jet magazine and it showed him in the casket. It was really sad, she was leaning over him kind of, and so the world saw.

TW: When you were in the store, you didn’t recognize them initially?

Kathy: No, okay. No, no, I didn't. I only knew their names. I don't think they had pictures out at the time. His wife only recently died and she said she lied, trying to make her husband jealous. They found papers in the sheriff's office downstairs saying that she should have been put in jail. But anyway, we got through that. I mean, we drove on and we stopped in New Orleans, we stopped in Texas, we stopped everywhere, from New York to Rhode Island.

TW: In that climate, going door to as a biracial couple…that’s very high risk.

Kathy: I was such a cute, adorable thing. I had long, beautiful hair and a cute little brown color, and my husband was white. He was so handsome. So when I rang the doorbell, if an older man answered….they saw me like, “Da-da-da-Da!” I was in. I mean, we were the best sellers.

Above: Clipping from TV and Entertainment Magazine, November 1978.

TW: Let’s leave Rhode Island for now and go on to your next chapter.

Kathy: Yeah. Get out of here, get out of here. My husband at the time, his brother was Roger Blunt. He's still alive in D.C., and that's how we went to D.C. in the first place. He offered my husband a nice job in landscaping. We got down there and found a beautiful apartment and I had to make sure the kids got to school, pick them up. All that. My former boss from WJAR, Arthur Alpert, he caught up with me and said, “You want a job?” I said, “Doing what?” He said you know, reporting and whatever at Channel 5, which is now Fox, but at that time it was something else. I forget what..I don't know, but now, it's Fox. Hmmm. Metromedia. My boss there, Hal Levinson said, “I'm going to have you produce Black News,” which was before...what's it called now? BET? Black Entertainment Television or whatever.

TW: What was Black News like and what else was going on at the station?

Kathy: I worked with Maury Povich, his show Panorama was the noon talk show. One of the first in the country, I believe. Delores Handy was my main reporter (at Black Reflections) and she was something else. I had to write the stories for the teleprompter so that my anchors, Delores Handy and James Adams...you know teleprompters work. She never liked the way I wrote stories, so we were always at odds. Oh and Al Roker, remember him? Al came from um, Washington State or maybe up there, Portland Oregon—one of those places way up there. He was funny, he was hilarious! Al was very kind, he had a big party at his house in VA when he was picked for the job of weatherman in NYC.

TW: It’s a really specific skill, speech writing. How do you make it feel natural, or how do you work with the anchors’ own personalities?

Kathy: Oh, we were like oil and water. The producer is in charge, but Delores was the big-time anchor somewhere in the south. Beautiful girl and very smart. Very, very smart, and she thinks I'm “merely the producer.” Well what do we do as producers? We research, we read every newspaper, we decide what's important in our area. Delores once said to me, “You're not smart enough to write for me,” and all the newsroom heard it—all the reporters and the boss, Hal, came out asking what was going on. I just said, “Dolores, f-you!” because I don’t cuss, and figured maybe she would understand. The whole newsroom started laughing.

The thing was, I was not really clever enough to deal with these people. You know, I was happy to do my job and try to do the best I could and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. We later renamed Black News to Black Reflections, and Washington DC is three-quarters black. So I had no problem finding stories. I was able to do my job and ignore all the extra crap.

TW: You have this really linear and logical way of working. Very head-down.

Kathy: I had no choice. I had to separate the crap. And I was never in fear of anything because I knew I could go to my news director. I would pick what was important and what I thought the viewer thought was important. You were really the eyes of the viewer when you're doing television, writing for television. I was very friendly and very nice, always smiling, and I remember whenever I went to interview people, they were very happy to see me because they were like, “Oh, she's going to tell the story correctly.” You know when I graduated broadcasting school in Boston there were thirty-three men and just two of us girls. Two. You had to prove yourself.

Above: Kathy’s winning doubles team from 1994. Note, this photo was edited to remove a sticker.

TW: Would you describe yourself as a competitive person?

Kathy: Oh no, no, no. Just driven. In tennis, for example, very few people are negative in tennis. I've got pictures of us in D.C., Houston, LA. We played in Boston.

TW: Who is the us/we here?

Kathy: The USTA Intersectional. We were the Mid-Atlantic team which included D.C., Maryland, and Virginia. Okay, it's not like Serena and Chrissy Evert, they're like 6 and up, their rankings. The Intersectionals were mostly ranked 2–5, and in the 40s, 50s, and 60s. That's the age group. We had the number one player. Her name was Margaret Russo, number one player in DC, in the mid-Atlantic. She was Australian and played when she was younger—against Martina Navratilova, with Chrissy Evert...all the big, big biggies and she won quite a few matches. Her husband was a big tennis teacher at the Fairfax Racquet Club. He was the best teacher.

TW: So you got into this in D.C.?

Kathy: Nope, I got into it in Rhode Island when I was married to Gerald (Blunt), because he was a big athlete. He was the Big Guy from East Providence High and wherever. When we got down to Washington a friend said, “Kathy, you want to go and play some tennis?” I ended up playing the Turkey Thicket. It was where everybody played after work. They had tennis clubs all over the place. So everybody took an interest in me because I was so nice to get along with. I didn't talk about anybody, I didn't, you know—nothing. So one of the guys, his name was Ted Utkins, and he used to love to play with me when we played mixed doubles. I was not good, but he knew I could learn. So he said to me, “Kathy, there's a tennis club in Bethesda, Maryland. It's an indoor club. It's two courts. It’s $10 an hour.” I had my little Thunderbird so I was free, could drive everywhere.

So once a week I went. I learned how to serve, I learned how to drop shot, I learned how to lob, I learned how to volley, and I got pretty good. That's when I started doing tournaments I played the first tournament against the number one seed and she beat me so bad. I was embarrassed. I went back to my practice.

At the time, Pauline Betz Addie was a big star down in the Mid-Atlantic. She played Wimbledon, she played all over and she used to practice with us. Pauline taught us how to drop shot and lob and we used to get frustrated because she would drop shot you, lob over your head...you have run back, run, run. And when we got that, she was very proud of us. We traveled as the senior league. We met people all over the place and everybody was so friendly. That’s when I had my video stores, so I could take a week every month and travel to play, no matter where I was. New Orleans, wherever...my husband, also. We had two stores. I ran one and he ran the other. The video stores were in D.C. Yeah, in Silver Spring and Rockville, Maryland.

TW: Any particular matches that stand out?

Kathy: So we were in Boston and Margaret [Russo] lost a match. I was playing doubles at that time. Never did she lose a match, no matter where we were. She's walking off the court and doesn't look right. And I said, “Margaret, what can I do for you, darling? You want some water?” She said she wanted to go and lay down. She went to bed and we all went downstairs, had a good time in the hotel, blah, blah, blah. This was the night before we were to leave and come to Philly, I guess, and same thing in Philly. She wasn't feeling well; lost her match. She was our number one player. We got to D.C. and she didn't play...she was taken to the hospital and she was diagnosed with whatever that thing is that you die and there's no return. What was it? It wasn't a heart attack, but it's kind of like that.

TW: A stroke?

Kathy: It wasn't a stroke...whatever it was. But she had that, and she died. I mean everybody was so sad, and her husband...Her husband was Gene Russo, a great tennis teacher at Fairfax Racquet Club there in VA.

Above: A photo of Kathy at one of her video stores in Maryland.

TW: So what got you into video store ownership?

Kathy: What got me into it? Let me think...one was being sold, in Silver Spring. The guy who owned it gave us such an unbelievable price because he wanted it to stay there. Then we bought one in Rockville the same way. Then Blockbuster came along and ruined everybody. So then we had to end up selling ours. There was a young boy who worked for me. Freddy Tello. You can look that up, I'm sure you'll find him. T-e-l-l-o. He was from Nicaragua. I think it was Nicaragua. Nice, sweet boy.

TW: What made you think of Freddy?

Kathy: He became friends with two really bad boys. They were all rich in this little town. Every once in a while we would see these boys come to pick up Freddy at the store. They were his best friends, good friends. I got the article somewhere, they of course interviewed me because he worked for me. I forget what the headline was, but the headline was like “Spanish,” or wherever he was from, “Boy Killed in Rockville.” Right near where the store was. They lived in this particular little area and a woman saw two boys driving a wheelbarrow with a hump in it, and that was Freddy.

They decapitated him. What happened was, supposedly, he was flirting with one of their girlfriends—plus being a Spanish kid and not being big time in Rockville—so they killed him. They took him to one of those vacant houses and they had a saw [content warning: graphic descriptions of violence] and they decapitated him, cut off his arms and legs, head, whatever, and I mean I was almost vomiting thinking about it. You know, I wasn't working for TV, I had my video stores and that was it…

[Kathy gets a text message]

Kathy: …and so...Oh. Somebody's asking me to marry him.

TW: You’re getting proposals texts?

Kathy: Just one! Yes, so...that story. I've got all those articles upstairs, I'm packing stuff away and I don't know where anything is. But that was the most traumatic thing I remember down there. And then finally we got divorced and sold the house.

Above: Kathy posing with her bicycle, 1983.

TW: Well that brings us back to East Providence, to your home just down the block from Myrtle. We don't always ask people specifically about the bar, but you are a beloved regular... What does the spot mean to you?

Kathy: They had their anniversary just over a month ago. I mean, there's other taverns and bars but it's a unique kind of place. There’s Robbie, and Melissa who works there. I mean, I walk in and it's like I'm in Hollywood—I'm a movie star! And I come up with stuff that's interesting that Natalie [Myrtle’s co-owner] likes. I feel like I’ve talked so much about myself here, but I do really want to say how wonderful and exciting Myrtle has been; what a nice addition to the neighborhood it is. The beautiful atmosphere, all the different music, everyone there is terrific.

[Kathy is now looking through a box of papers]

When my daughter was in town, we did a review. My daughter Pam’s a singer, she lives in Chicago and I’m a poet. I thought, what if we do a thingy with her, me doing poems and her singing, you know? Natalie said, “You know what? That would be great and I can play the piano to your poems.” It was so much fun. She's such a good piano player, Natalie. Such a good piano player. When I was being dramatic, she'd do the piano all dramatic. Why can't I find it? The one I wanted to show you? Oh, here it is. Yeah, this is what I came up with.

TW: Were you doing poetry from a young age?

Kathy: No, no. Most of these poems are written from familiarity with people that I met in life. Like when my good friend passed away, I wrote a poem. He was head of the NAACP in East Providence and we became real friends, I mean good, good friends. What was his name? George Lima. And this [holding a paper] is the one that Natalie fell in love with. I was just sitting around thinking, you know, I needed to start writing some stuff.

TW: Could I ask you to read it?

Kathy: You want me to read it? Yeah, okay, my eyes are terrible. Oh, you know, Natalie is one of my favorite people. She's just a fabulous person. Isn't that weird, because I've only known her for a year? Okay, you want me to read this yeah?

What do you think?

When you hear a baby cry

When you see a bird fly

Do you get a tear in your eye?

Or…

Do you wish you could cry like a baby?

Do you wish you could fly like a bird?

Or…

Do you just wake up!

Bonus Documents

When asked for photos to go along with this interview, Kathy gave us a neon green shopping bag full of treasures. Below are some of our favorite finds; you can click them to enlarge.

Marketing Agency, with Sheida Soleimani

Sheida Soleimani (شیدا سلیمانی) is an Iranian-American artist, educator, and activist, as well as a federally licensed wildlife rehabilitator. Born in Indianapolis, she grew up in the 90s, raised as a Marxist atheist in the Bible Belt. Her parents arrived as Persian political refugees, having escaped oppression related to their pro-democratic activism during the ’79 Iranian Revolution. Since then, Sheida has become a widely respected artist and community organizer; she recently participated in a talk right here in East Providence, at Odd-Kin as part of the FABRIC Arts Festival. We talked about art, birds, and life.

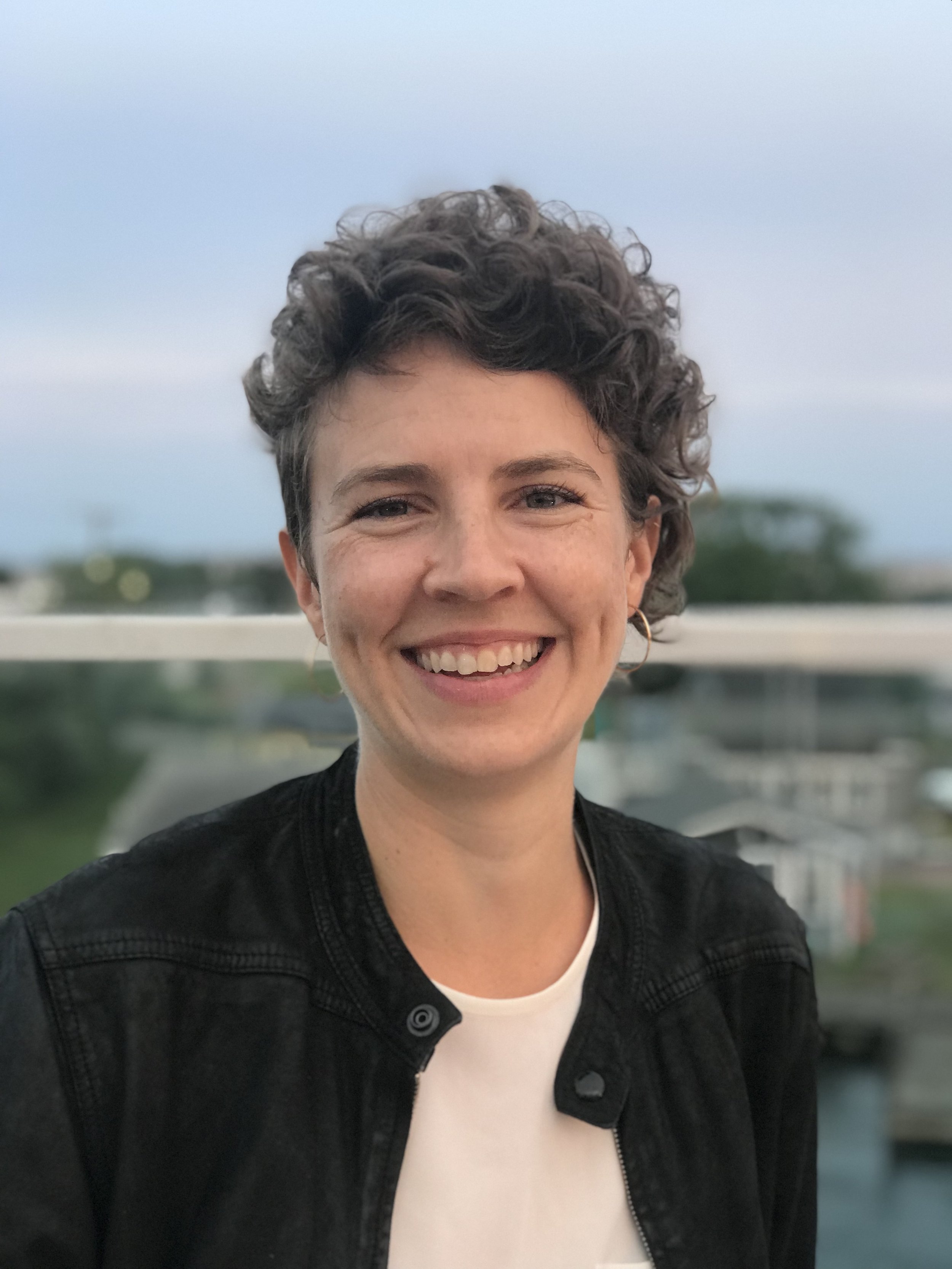

Portrait by Shana Trajanoska

Sheida Soleimani (شیدا سلیمانی) is an Iranian-American artist, educator, and activist, as well as a federally licensed wildlife rehabilitator. Born in Indianapolis, she grew up in the 90s, raised as a Marxist atheist in the Bible Belt. Her parents arrived as Persian political refugees, having escaped oppression related to their pro-democratic activism during the ’79 Iranian Revolution. Since then, Sheida has become a widely respected artist and community organizer; she recently participated in a talk right here in East Providence, at Odd-Kin as part of the FABRIC Arts Festival. We talked about art, birds, and life.

The Well (TW): Hello! You got any wild stories?

Sheida Solemani (SS): Lots.

TW: Hah, okay. We’ll start with the basics and see where this goes. What was growing up in the Midwest like?

SS: It was wild. It's a beautiful place to grow up, but being a Middle Eastern kid post-9/11 made it really difficult. By virtue of refusing to make nice with their neighbors—think of being the only people of color in a midwest farm town filled with corn and soybean fields—and in many ways refusing to assimilate, my parents introduced me to principles and beliefs that I aspire to in my life and my work: speaking frankly to power, rallying around difference, and confronting ignorance and misrecognition.

TW: Can you give a specific example or two?

SS: One Halloween during the Iraq War, my dad briefly became notorious for constructing a scene involving George W. Bush in a casket. Another memorable moment from childhood was when Touchdown Jesus—a really large foam sculpture of Jesus with his arms out in front of him, built in front of a mega-church—got struck by lightning and caught fire. My baba saw it on the local news right after it happened, and we drove to go see its burning remains. My baba has a booming laugh and cackle; I can hear him laughing with joy to this day in my memory, as we all watched Jesus burn. A few years later, he was 'resurrected' and rebuilt again, much to our dismay.

TW: Very goth! Your family’s been involved in your art practice recently, we’re thinking of the Ghostwriter work.

SS: Working with my parents is amazing. We're all really close, and so much of who I am is informed by them and all of the stories they have told me. When we work together, we bounce ideas off of one another. My maman will help pose my baba, or help me build the backdrops. My baba will always question my maman and I about our 'intention' and if it is coming across in what we are making. I feel really lucky that they are so supportive and so into being a part of the process.

Above: Young Sheida with a baby raccoon. “This is what rehabbing in the 90's looked like. This photo is an example of what not to do. Please do not attempt to cuddle wild animals or allow your children to do so ;) ”

TW: That’s great, it sounds like a real point of pride.

SS: [I am] really proud of the work I have been making with my parents. Also really proud and excited to be building my passion and work as a wildlife rehabilitator into a full blown organization. I feel the most proud when I can release a bird that I treated back into the wild where it belongs.

TW: What’s your official title when it comes to bird work?

SS: I am the Executive Director of Congress of the Birds, the state's only wild bird rehabilitation clinic and release center. We just got our non-profit status this year, and are gearing up to build a bunch of enclosures on 42 acres of land that were just donated to us. Last year, we took in over 1,500 birds, and this year I think we'll have over 2,000.

TW: What’s the process of getting a Federal Migratory Bird Rehabilitation Permit?

SS: Long! And really intense! I've been a rehabber my whole life, but I've been state permitted in RI since 2015. The federal permit is a really intense application that requires a lot of prior certifications and permits, as well as letters of support from rehabbers and vets in the field. It was not an easy permit to get!

TW: And where’d you get the 42 acres?

SS: We were really lucky to get a private donation from someone who is passionate about the work we are doing with rehabilitating the birds. It came as a total surprise! I was completely shocked when the donor approached us about it, but am so grateful to be given the space to release the birds we rehabilitate.

TW: Before the birds are in your care…where are you finding them?

SS: My phone number is public, so when someone finds an injured bird, they can easily find my info online and call me. I give them instructions on how and where to drop off the bird to our clinic for care. I'm getting around 50 calls or so a day at this point!

A lot of my getting to know Rhode Island's every single little corner has been through bird rescues. Notable bird rescues in EP include an adult Osprey that was in an industrial park on the water, a Double Crested Cormorant near the Henderson Bridge, and a Common Grackle with a broken wing hiding under a car off of Anthony Street.

Above: Dissident from Ghostwriter

TW: How do you think about these two practices—art making and wildlife rehabilitation—in relation to one another?

SS: I think all three facets of my practices are part of my world that I have built for myself—I don't differentiate being an artist or rehabber or professor from other things in my life/world. Foraging and cooking, making dumb stuff out of clay, collecting records, hoarding plants. Those are all just extensions of my base interests. I guess one thing many people don't know is that I am a classically trained violinist who left the conservatory because it had too many rules.

TW: What about early on in life...when did you start making things you understood to be art?

SS: I remember thinking I was making “art” when I was taking my first film photography class in high school. At the time, I was super obsessed with the concept of memento mori and time. I wanted to tell a story, which I never had really thought about doing visually before, and I made a tableau photograph of a wall clock that I placed a large dead moth on. The shadow of the moth was covering some of the clock, obstructing most of the numbers—it was very angsty, but I had this whole 'time is running out' thing going on at the time. It was exciting to feel like art could tell a story.

TW: Storytelling is still very central to your practice—even when abstracted, it’s rich in narratives. This is a big question for limited space but, what are you primarily concerned with conveying?

SS: Finding clever ways of seducing viewers to engage with a work is something I think is especially important in the art world, which is so profit-driven and so prone to turning a blind eye to entrenched inequality. In sweeping away the West’s blinkered, Orientalist view of the Middle East and centering the spectator’s gaze on actual ongoing drivers of injustice and inequality, I seek to put in the aesthetic hot seat those who continually evade the scales of justice. At the same time—and this is getting back to repair and care—I am just as concerned with giving the marginalized (including the non-human) visibility and agency within my work.

TW: When you’re creating a series like Medium of Exchange, do you start with pure research (OPEC email leaks, international press), or by playing with images and finding stories as you go?

SS: I always start with research before coming up with an idea. All of my images are inspired by specific events—historical, political, familial—and those events are always the jump off point. I then get to learn more about those events through different forms of research- whether those be visiting archives, reading documents, or transcribing and translating oral histories. From there, I start creating sketches and think about what objects and images can be put together to tell the story I am trying to portray. Once I build up my tableaus (days to months depending on the composition), I photograph everything, and the photograph serves as the final piece.

Above: From Medium of Exchange. Photo: GDP, Angola

TW: We like to ask artists how they’re getting by financially—is that cool?

SS: I've always had to work to make a living, and have had some really rough times in my life. One year while teaching adjunct, I was buying expired medical equipment on eBay—I'm type one diabetic. [Today] I'm lucky to have a solid job, and just got tenure at Brandeis University where I am an Associate Professor. My art pays some bills for sure, but I can never rely on it as a steady income as someone with a chronic illness, so I'll be teaching for the rest of my life. Thankfully, I also love teaching, so that helps. Basically, a stable job with university health insurance is much better than expired meds on eBay.

TW: What’s something you’ve learned by teaching, or from students?

SS: When I started teaching at age 25, I was really young. I made friends with many of my students, and while I value those friendships immensely now, I realize that distance is needed to be a good and fair educator, and one that can create distance between work and life.

TW: Teachers always have great reading lists—give us some assignments!

SS: 100 Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, The Blind Owl by Sadegh Hedayat, and The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov.

TW: Has any of your work in education, art, or with birds led to travel? Any notable trips that made an impact?

SS: I travel often, and to many different 'far away places.' I'll go with the most remote. Visiting the Lofoten Islands in Norway was one of the most remote places I have ever been, and we visited during the winter months for my birthday. I was hoping to see the aurora, and on the last night, I got to see the green and orange lights 'dancing' in the sky during a solar storm.

TW: What’s something you’re currently aspiring to?

SS: Maybe one day I'll learn how to leave time for self care. Until then, I rule my life by my baba's motto, “Comfort = death.”

TW: Readers, now for something a bit different.

Sheida has a GoFundMe page up to support her effort to build an avian release center for Congress of the Birds. Below, we’ve excerpted some info from that page.

Help Build an Avian Release Center for Congress of the Birds

Above: Getting ready to examine an injured Great Horned Owl, photo by Jessica Rinaldi for The Boston Globe, via GoFundMe

Congress of the Birds has expanded rapidly in the past year, becoming a 501(c), training over 50 volunteers, receiving over 2,000 avian patients and getting 42 acres of secluded woodlands in Chepachet. Their organization runs 24/7; they never turn away an injured or orphaned bird, and volunteers pick up birds from around the state. Now, they need your help!

A release center means that rehabilitated patients will have the best chance of success once released into the wild. To create a center, the Congress needs to build aviaries and flight enclosures that help birds build up their pectoral flight muscles—without proper conditioning, a bird may not be able to survive if it’s “hard-released” into the wild. In other words, they get to practice flying and acclimate to their habitat before going out on their own.

The Congress is not state funded and has no institutional or corporate donors. This project is relying exclusively on donations from the community and, this is big: every dollar donated is being 100% matched by a private donor. Read on and consider chipping in to help this project—and its patients—take flight.

Place Setting, with Kara Stokowski

Kara Stokowski is queer feminist artist and educator whose practice involves DJing, event production, music video creation, collage, and more. A passionate and radical youth arts educator, her work has inspired countless kids at The Beam Center in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Kara Stokowski is queer feminist artist and educator whose practice involves DJing, event production, music video creation, collage, and more. A passionate and radical youth arts educator, her work has inspired countless kids at The Beam Center’s camp in New Hampshire and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. You’ve perhaps caught her playing tracks in Providence at Dyke Night, at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, and right here at Myrtle. Kara approaches fun and joy with a level of dedication matched only by like, Robert Caro’s interest in bureaucracy. We chatted via emails in early October.

TW: Hey Kara. We’re going to start by asking about a track you produced in 2009, The Glow Instrumental. It’s like, grime, 8-bit/glitch, hyperpop and a touch of Wrong Way Up, maybe? What were you listening to in 2009?

KS: Wow thanks! I probably made that in Tony’s [Antony Flackett] Beat Research class at MassArt. I was listening to a lot of video game music and sound effects and was enamored with analog synthesizers.

TW: Up at MassArt, you co-produced a year for Eventworks. You had Future Islands play?

KS: I jumped into Eventworks because I was completely in awe of what the previous students had done in 2008. The Baltimore Round Robin show totally melted and reformed my brain. I wanted all of our events to feel like the floor fell out and the ceiling was coming down. I wanted everything we did to last all night long. I was often disappointed, even though we pulled off some monumental shows including Future Islands, Dan Deacon and this crazy VJ festival. There were so many forces pulling me in different directions at that time and I didn’t always have the clearest vision or intention. It’s really easy to be taken advantage of in that situation. I just went back to MassArt in September for the opening of Displacement at the MassArt Art Museum. I checked in with the SIM major studio, second class of the year! Eventworks had just put on a rave, there are lots of DJs in the studio right now, very deeply and rightfully skeptical of me, a 30-something lady playing records in the white cube space at school.

TW: When we think of you as a DJ, Pink Noise comes to mind. Tell us about that.

KS: I love to throw a party. I wanted there to be a space for women who were DJs or made electronic music to be able to DJ for other women, at a party that felt fun and safe and queer. I wanted Pink Noise to be a place where people could try out DJing for the first time and feel supported. I also was really turned off by the darkness and self seriousness of the dance music scene in Boston at that time and really wanted to add some play and radical joy. Reflecting back on it now, I think I had a lot to prove: I was coming out of a deep grief, I put a lot of pressure on myself. Pink Noise was a way to focus some nervous manic energy. I learned so much! It was a real relief to wrap it up in 2016 and give space for someone else to create something special.

Above: Kara DJing at the Institute for Contemporary Art, Boston

TW: Actually, let’s go back a sec. How did you end up at Mass Art, and in the event production world to start?

KS: I’ve been a theater kid, a ska fiend in high school, a bit of a computer nerd. I went to ska shows every weekend when I was in high school at the Flywheel in Easthampton. I went to community college in Greenfield and then MassArt to make more art with computers and tech. I’ve been a childcare provider, an educator. I’ve been a union organizer, a striking worker. I love a spectacle, I love producing events, I love gathering the masses for any kind of ritual or celebration.

TW: Is this the world you met your partner, a local clammer and sax legend?

KS: I met my partner Joe DeGeorge on the beach 9 years ago. I love how we support each other.

TW: And you moved here, to Providence, a few years after?

KS: I had been visiting friends and lovers in Providence since 2013, and finally made the move in 2018. It’s a perfect distance from all the places in New England that I visit frequently. I love the big city/small state vibes.

TW: What’s in Kara’s Guide to New England?

KS: These are mostly from this summer’s travels:

Beede Falls, Sandwich NH - fave waterfall and day off spot when I’m at camp

Look Park, Florence MA - My hometown park

Coney Island Hot Dogs, Worcester MA

Provincelands, Ptown MA

Dinosaur Footprints, Holyoke MA

TW: Another reason you travel around is your work as a wedding DJ. It’s quite different from club DJ world…how have you approached it?

KS: I did a few weddings in 2019 and then, everything that was on my calendar for 2020 got rebooked to 2021. By that time I had gone from dipping my toe in, to diving into the deep end with a full calendar of clients. Wedding world is crazy. Wedding DJs (especially) have this notorious reputation for being the worst—weird dude energy, wrestling announcer vibes, pretentious and snobby with lots of “gotcha” moments. I just don’t believe that you need any of that to have an amazing wedding with a killer dance party.

Above: Kara in her MassArt Eventworks days.

I work with clients who are passionate about music, so that’s what we focus on. I feel very lucky to work with queer folks and creative people who give me a lot of trust and it’s such a joy to see them let loose and go crazy on a day that can be so stressful. Joe and I did a 80’s theme gig over the summer where he played live sax solos on some iconic 80s tracks and we’ve got a couple weddings booked with a live sax add on next year, very excited for this.

TW: After those gigs, what’s on the drive home playlist?

KS: I listen to the radio alot in my car. We love playing “name that composer” to classical music if we’re on a trip. I listen to jazz when it’s late at night near Boston. If I’m getting drowsy, it’s time to put on showtunes. I’m currently in this Patti Lupone phase thanks to this video of her on Joan Rivers.

TW: What’s your favorite medium to play out on—records, midi controllers, etc?

KS: I love it all! I think I really like the limitations that a crate of records brings. You only have what you have to work with, and it’s all gotta work!

TW: Since your weekends are usually booked with weddings, what do you do around here on a weekday? What’s poppin’ on Tuesday night?

KS: Well on Wednesday nights I’m usually at Hot Club. They have Name That Tune, and I am very, very good at Name That Tune. I welcome any challengers to name more tunes than me on a Wednesday night at Hot Club. Shout out to Kelsea, our incredible host who comes up with unique playlists every week.

TW: No challengers here. Do you have visual art practices, also?

KS: I make a collage every day in November. I love taking the winter to work on visual practices. It’s meditative, it’s processing big feelings. I also love making music videos.

TW: Do tell.

KS: I had to rewatch some of these to remember them just because I made them like 5 years ago. The stranglehold that Deee-Lite had on my entire vibe is obvious, lol. You ever see the Groove is in the Heart video and decided to base your entire personality on it? For this Gauche video (below) I wanted the video to clash a bit with the downer lyrics. We repeat these things so much in capitalist culture: we’re running out of options, we’re tired, what is the point? It becomes goofy! And so the video is kind of this exaggerated exasperation of toys and neon and colors and trash and landfills and oil spills.

For this La Neve video, I just wanted it to be really cunty. The comments are SENDING ME. Wow, bless. I used this colorful big oil propaganda vid from the 50s for some of the green screen background to insert this idea about an energy source that seems so stable, but is actually pretty fragile. I like contrasting that with the stability of our natural world, the challenge we often present to it to keep on living and the many ways that it does despite everything. Sometimes just living is the best revenge.

TW: This isn’t a great transition but, just remembered your bios often mention a gold prosthetic on your leg. We’ve known you a bit but don't know the story there.

KS: Oh, I wear a prosthetic on my right leg. I was born missing a bone in my lower leg, so I had an amputation when I was 9 months old. I’ve worn a prosthetic ever since. All bodies are absolutely amazing and mine is no different.

TW: Agree! Heading into fall and winter here—as a nod to the disappearing warm weather, what’s a great beach book?

KS: Okay. If you really want to know what my summer beach read was, it’s this book, Life in a Medieval Village. It’s not cool, not very sexy—but I loved it! Peasants: they’re just like us! This really gets into some of the pettiness and small acts of rebellion that people who have very little power can get up to. I also read The Hotel New Hampshire this year and it’s so weird and beautiful. I also really like Britney Spears’ memoir. I’ll read just about any memoir.

Above: Out, into the night! Kara around age 6.

TW: What’s the next chapter of your own memoir? What’s coming up?

KS: November and December are for rest and recovery from the wedding season. I’m always down to DJ for a cause and I’ll be spinning at the Sojourner House Masquerade Ball at the Graduate in Providence on Friday Nov. 22nd. I might be at the Dirt Palace holiday sale selling polymer clay jewelry in December, and then on January 3rd, I’ll be back at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston for First Fridays from 6-9pm. Members can reserve free tickets and it’s a fun time with some old art. I’m really into the Italian renaissance wing right now, especially this painting. And I’m definitely more open to collaborations and DJing around town in February and March, before weddings pick back up again in April.

TW: Thanks Kara, you’re the best!

*

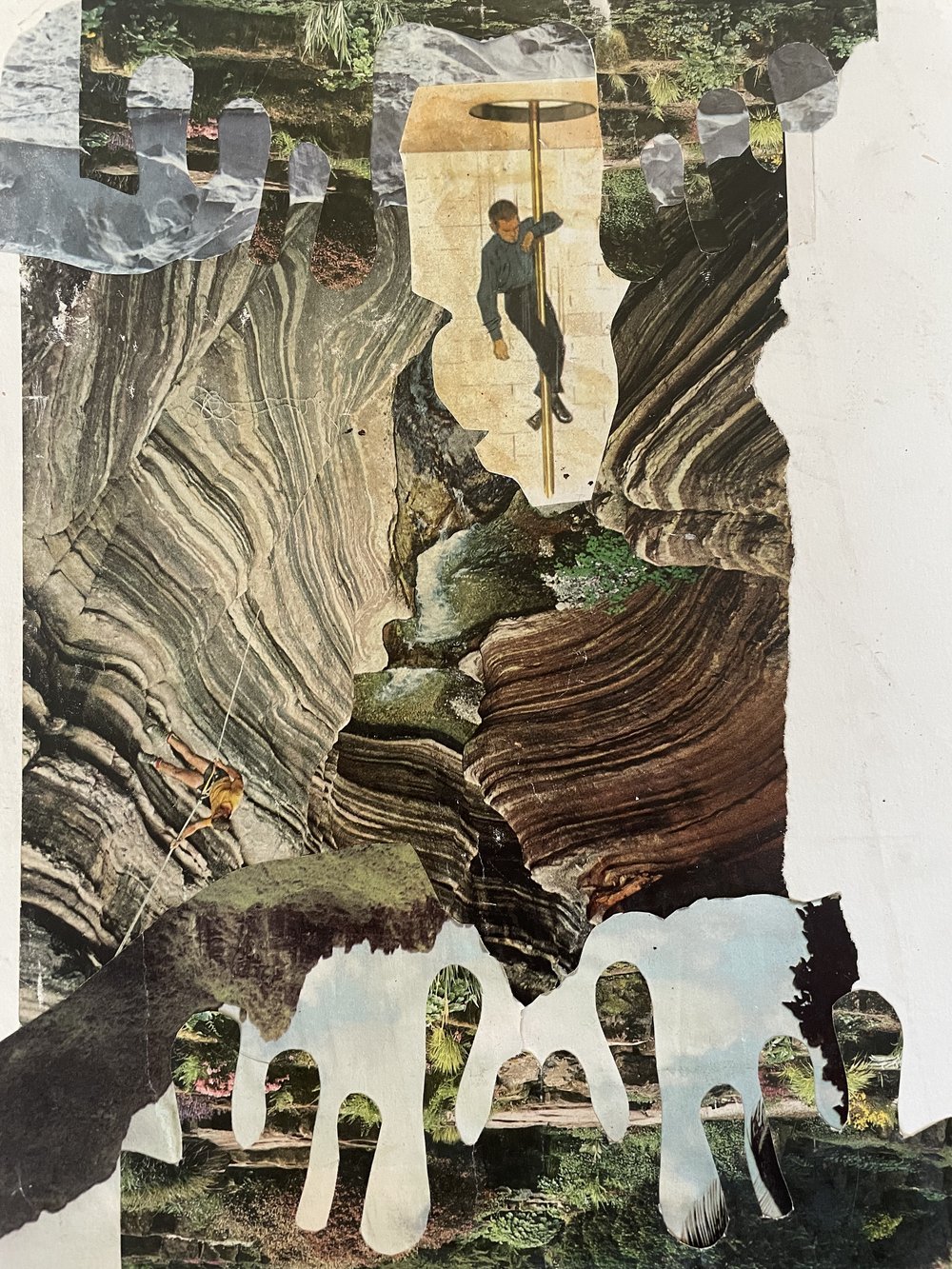

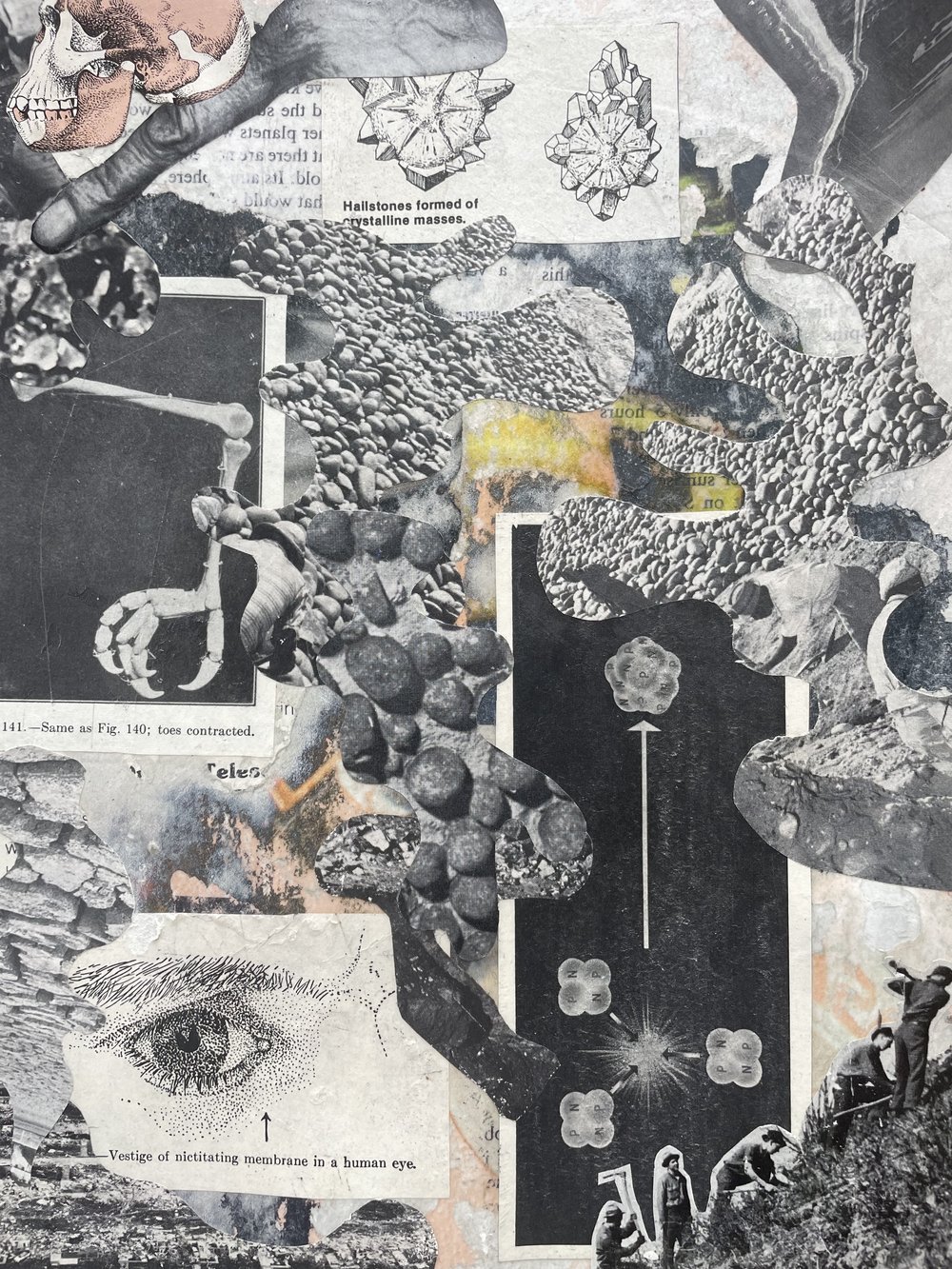

Readers, below is a selection of collages Kara’s made over the years. If you’re looking for collage source materials, The Well suggests the upcoming Rochambeau Library Fall Book Sale, October 30–Nov 2.

Pressing On, with Lois Harada

Earlier this week, we were visiting the Providence Public Library and stumbled upon a new show by artist Lois Harada. Pied Type: Letterpress Printing in Providence, 1762–Today explores the history of commercial printing in Rhode Island, and will be on view through January 11, 2025. Locally known for starting the #RenameVictoryDay project, Harada’s larger practice references a range of histories, aesthetics, and ideas, from WPA Posters to Sci-Fi authors Butler and Bradbury.

Lois Harada. Photo by Rue Sakayama.

Earlier this week, we were visiting the Providence Public Library and stumbled upon a new show by artist Lois Harada. Pied Type: Letterpress Printing in Providence, 1762–Today explores the history of commercial printing in Rhode Island, and will be on view through January 11, 2025. Locally known for starting the #RENAMEVISTORYDAY project, Harada’s larger practice references a range of histories, aesthetics, and ideas, from WPA Posters to Sci-Fi authors Butler and Bradbury. Works address topics like language, non-verbal communication, xenophobia, and Brett Kavanaugh head on. Great stuff!

TW: Hello, Lois Harada. Who are you?

LH: I am an artist based in North Providence, RI. Much of my work is based on my family's history of Japanese American incarceration.

TW: Could you elaborate on that?

LH: My paternal grandmother and her family were forcibly removed from their home outside San Diego to an incarceration site in Poston, Arizona from 1942-1945. They settled in Salt Lake City afterwards where she met my grandfather—also Japanese American, but excluded from incarceration due to being from Salt Lake City and not a coastal area. This history really was not talked about in our family. My dad learned about it in his tenth grade history class and proceeded to ask my grandmother about it when he returned home. She said something like, ‘Yes, it was a terrible thing,’ and then moved on. I started to make work around incarceration the year after she passed away but my family has had more conversations about it now and are helping me research.

TW: In 2019, you made a poster related to this that simply read #RENAMEVICTORYDAY, which led to a good bit of press, and a petition from Amanda Woodward. Tell us about that.

LH: Since 2019, I've been making work to encourage RI residents to rethink the naming of Victory Day—the official title on the books, but most residents call the day VJ Day or Victory Over Japan Day. I do not want to take the holiday away or take recognition from veterans who served in World War II but do want to think of a more inclusive name to the day. Asian Americans often feel isolated or singled out on this day and most residents use it as a day at the beach. Legislation has been slow—veterans lobbying groups have a lot of sway in the state.

TW: You brought the message right to the people, at the beach.

LH: In 2020, I hired a banner towing plane to carry #RENAMEVICTORYDAY across beaches in RI on Victory Day. It was a big project for me in scale and in cost and I raised money from supporters via social media to help fund the project. The plane made several loops over beaches and it was fun to hear reports of boos or cheers from the beaches.

Above: #RENAMEVICTORYDAY plane. Photo by Rue Sakayama.

TW: Was this method of message delivery more about like, hijacking a common beach advertising thing, or a nod to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

LH: I didn’t realize that as part of the initial project, but it’s hard to separate it from the history. I knew that most residents used it as a beach holiday so wanted to take the project directly to them. I’m not sure if anyone at the beach interpreted it that way on the day of. I am also very interested in thinking about spinning common advertising forms and these planes often carry insurance or beverage ads.

TW: You mention legislation here’s been slow, in part due to veterans’ lobbying. What do you think the pushback’s all about? We want to be respectful, and assume it’s rooted in deep trauma but, we also can’t ignore outright racism. There’s also Rhode Islanders being a bit resistant to change about anything, really.

LH: I can’t quite figure out what the pushback is—it seems like there is this golden idea of World War II that people are quick to defend, including veterans from other conflicts and family members. I was encouraged by the vote removing ‘Providence Plantations’ from the state name but that seems to have bolstered many people against changing Victory Day since it’s a ‘woke’ issue. It’s difficult to have conversations with people with this viewpoint too as there is nowhere to engage. We do have some veterans supporting our bill but those in opposition tend to outnumber them. I once got advice to just wait till everyone from that conflict had passed away but I’d like to change the bill while there are still survivors of Japanese American incarceration surviving too.

TW: So you have a new show up at the Providence Public Library, Pied Type: Letterpress Printing in Providence, 1762—Today. Like #RENAMEVISTORYDAY, it’s rooted in history and research but now, looking at the physical history of your practice. How’d it all come together?

LH: I applied for a Rhode Island Humanities grant last fall and was awarded the grant near the end of the year. I worked with Dirt Palace Public Projects as my fiscal sponsor and got the project up and running in March or April of this year. I spent a lot of time visiting Special Collections at Providence Public Library with the Director, Jordan Goffin. It was very hard to winnow down materials—I could have spent a year just looking at everything. I knew we had a certain number of cases to choose from and the exhibition started to take shape by slowly identifying what fit together in each case and the overall ‘story’ of the exhibition. I realized we had some holes in material and reached out to some partner organizations who were very generous in loaning materials. Jordan was crucial in those connections as he was known in the archive and museum community.

Above: Installation detail of Pied Type. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Writing labels and the catalog did take a good amount of time too especially since I wanted to control the design and most of the printing. The experience was a great opportunity to try curating on a larger scale—I’ve done some small group exhibitions in the past, but it’s a totally different set of muscles than making art and putting it in a gallery.

TW: You’ve been doing print work at DWRI Letterpress for many years; how’d you end up there and what’s the shop meant to you?

LH: I met [shop founder] Dan Wood as a RISD student in 2009—he had just started teaching the letterpress printing workshop in the Printmaking Department. I was so keen to learn the medium that I took a class at AS220 the year before so I was excited to build on those skills. I started working part time for Dan about a year or so later and have seen the shop move and grow in terms of employees and the type of projects that we work on. Dan is always very supportive of other printers and is very generous with his own work (if you’ve seen him right after printing an edition, he’ll usually hand you a print!).

TW: For those who have never seen a Linotype machine, a press, etc in person, could you give a quick overview of your favorite few pieces of in-shop machinery? And outside the shop—walk us through the process of how one makes a custom souvenir-coin vending machine.

LH: I love printing on the Windmill at the shop. It’s a great commercial press that you can print around 1,000 prints in an hour…if everything is running well. I printed the show postcards on a Windmill. I am sadly mostly on the computer at the shop so this was also a great excuse for me to get on press and out of design or client management for a bit.

LH: The penny press was also grant-funded and I had some fun conversations with the grant officer about telling the story of that piece in the budget (i.e. maybe it doesn’t take the majority of the budget!). My sister is great at the internet so she helped me sleuth out the best place to order. I have a used machine; new machines were about four times the cost. They are usually rented too and not purchased outright.

TW: Grant writing is a whole unique skill set. From the time you began applying for grants to present day, what are some pro tips and lessons-learned you can share here with first timers?

LH: It can be super easy to be discouraged by the grant writing process—I’m not telling you about the tens or hundreds of things I apply to and don’t get, you’re just hearing about the things I get! I try to think about always of simplifying my writing and getting out of the mode of ‘art talk’. Could my non-art parents understand my grant? Have I very clearly laid out how I will accomplish a project; even small things can help here. Budgets are also a great place to tell more of the story and show that you know how to get things done. I often ask for a reader, too. If the grant needs a letter of reference, I usually write a letter to 80% completion that I can share with a recommender so that they have all the stuff that I’m working on right now that should be mentioned for the particular application. Sme grants don’t allow this but I find that most people being asked for a letter find this helpful. I’m happy to read your grant or have coffee, email me!

Above: Villa Adriana aquatint, from Harada's time in Rome.

TW: A lot of the work we’ve been discussing is Rhode Island-specific; you ever get out of here?

LH: I took a semester abroad in Rome while I was at RISD; the school had this amazing campus in Rome for many years. It started as a year long program then switched to a semester when I went. They just ‘sunsetted’ it and turned over the lease on the building that housed students and studios. I went with about twenty other RISD students in different departments. While there was a print shop there, I spent a good amount of time cutting paper into sketches of different sites that I was seeing on a daily basis.

It was the longest I had been away from home and though scary, felt like a real chance to get to know a new place in a way that shorter trips couldn't accomplish. Grocery stores and markets became a favorite there and are still my favorite spot to check out on any trip.

TW: What’s your favorite local grocery shop? Other favorite local things, too if you’d like.

LH: East Providence is home to my favorite grocery store, Asiana. Sun and Moon across the way is also a favorite. I've celebrated several birthdays and sunny days at The East Providence Yacht Club. Odd-Kin is one of my favorite contemporary art spaces around right now too!

TW: It’s someone’s first time at Asiana—what are some must-try items, brands?

LH: They have a great selection of Korean and Japanese grocery items so I always shop there to fill up my pantry with rice and other staples, including instant miso soup or ramen or the ban chan from the fridge (the tasty side dishes served with a meal in a Korean restaurant). Freezer dumplings too!

TW: Back to Odd-Kin...we interviewed Kate a bit back and know you worked with her on the My HomeCourt project. Can you walk us through the process of initially visiting Davis Park, researching, and working with community stakeholders—and what you hoped to achieve with that project?

LH: Kate McNamara, who runs Odd-Kin, is the Executive and Creative Director of My HomeCourt and I worked closely with her and Jamilee Lacy (the former director) on this project. Davis Park was close to my old apartment in Mount Pleasant and is used by the neighboring middle school, VA, community garden as well as residents from around Providence. I spent some time visiting the park and My HomeCourt helped to gather community feedback and surveys. The park has an overlap with many languages, and I wanted to reflect that in the design through words that you might hear on a basketball court (play, together, run etc.). The letterforms were mostly printed in wood type and then scanned with the exception of the Khmer which I stitched together from other letters. I am happy with the result and love seeing people interact with it on a daily basis.

Above: Davis Park Mural, 2022. Photo by Off the Ground Drone Services (FB)

TW: Way before you were doing murals on basketball courts and flying planes over beaches—what do you remember making as a kid? Like what’s the first ‘ah-ha!’ moment with the arts?

LH: My mom is a very crafty person (she's a quilter and avid puzzler too) and she always had fun activities for my birthday parties. One year we made plaster of Paris magnets from little molds and I remember being so entranced by the ability to make a multiple. I've been a printmaker since then!

TW: What was growing up like?

LH: My earliest memories are of family. My mom is one of ten and there were always dinners and events full of cousins and aunts and uncles. My dad and I were big fans of the drive-in theater and saw several Fast and Furious movies there. He is also an avid fly fisher and spends hours crafting flies. [Well’s addition: a great story about fishing flies]

My high school art teacher had an MFA in Printmaking and set up a studio in our classroom. I was lucky to have etching and lithography available during class and he encouraged me to apply to school at RISD.

TW: Are there other artists working with the idea of multiples / editions you’ve found inspiration in?

LH: There’s a Sol LeWitt series of etchings that are these really rich black fields with small white shapes. I’m checking if I can find them, I saw them at a print fair in New York when I was a student. There was something super striking about seeing a wall of similar, or the same print repeated over and over that’s always stuck with me which I think informed that piece.

Above: Young Lois, excited to be hiking. "I do not support the Dodgers, I don't know where that hat is from."

TW: As an artist who works so heavily with text, we have to ask you about other texts. Are there books, poems, etc that mean a lot to you?

LH: Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler. I read this for the first time in 2020 and think about it often. Also, Ubik by Philip K. Dick—I'm a big lover of sci-fi!

TW: Parable is highly quotable. “Embrace diversity. Or be destroyed.” What would you pull out as a favorite?

LH: The whole thing is so moving—I couldn’t put it down. It had so many parallels to the election and quotes felt like they could have come directly out of the news. It doesn’t seem like we’re that far away from the world depicted in the book too. I’m realizing now that the quote that sticks with me is from Parable of the Talents:

Choose your leaders

with wisdom and forethought.

To be led by a coward

is to be controlled

by all that the coward fears.

To be led by a fool

is to be led

by the opportunists

who control the fool.

To be led by a thief

is to offer up

your most precious treasures

to be stolen.

To be led by a liar

is to ask

to be told lies.

To be led by a tyrant

is to sell yourself

and those you love

into slavery.

TW: Yow! Less than a month out from the election, that one really hits. Thanks for sharing it. So, what’s coming up? Where can people find you?

LH: We have a panel of letterpress printers on 11/12/24 from 5:30 to 7pm at PPL. Jacques Bidon, Andre Lee Bassuet, Dan Wood, and I will be talking about how we're using letterpress techniques in our practice (the first three have work in the 'contemporary' case of the exhibition!). The panel will be moderated by Director of Special Collections at PPL, Jordan Goffin. He and I will also host a hands-on print workshop on the last day of the exhibition on January 11th from 10-12pm.

And Social Justice for All, with Sussy Santana

Poetry is Sussy Santana’s main medium for creative expression. She makes "llamados," or "calls" to community members and artists collaborators to participate in collective performance. Santana is Project Manager for the Providence chapter of Arts for Everybody, author of Pelo Bueno y otros poemas (2010), RADIO ESL, a poetry cd (2012), and the chapbook Poemas Domésticos (2018) and in 2020, was the first Latina writer to win the MacColl Johnson Fellowship.

Photo by Giovanni Savino

Poetry is Sussy Santana’s main medium for creative expression. She makes "llamados," or "calls" to community members and artists collaborators to participate in collective performance. Santana is Project Manager for the Providence chapter of Arts for Everybody, author of Pelo Bueno y otros poemas (2010), RADIO ESL, a poetry cd (2012), and the chapbook Poemas Domésticos (2018) and in 2015, was the first Latina writer to win the MacColl Johnson Fellowship. You can catch her as a special guest this October 19th at Grant Jam ‘24, a free panel talk night at AS220 hosted by the Myrtle-supported Awesome Foundation Rhode Island.

TW: Who was your first audience?

SS: Rocks. I vividly remember being little, maybe five or six, and picking up rocks in my neighborhood to bring them on the bus with us when we went out. My mom just asked me the other day, if I remember doing that! We didn't have a car so we took public transportation wherever we went. I would pick up tiny rocks and tell them they were going to visit their cousins in another town. I had a whole little ceremony with them about how they had to say goodbye to everyone and go on a new adventure, visiting their other rock relatives. I would get emotional when it was time to part ways, but off they went to rock on.

TW: What does East Providence, land of sandstone and shale, mean to you?

SS: Providence is my home, at this point in my life I have lived in the United States longer than I lived in my birth country, and a lot of that time has been spent in Providence. While I go back to the Dominican Republic almost every year, when I think of "mi casa," I'm thinking PVD. When I think of East Providence, I think of how many hours I spent in the parking lot of the Philharmonic building, waiting for my oldest daughter to get out of her RI Children Chorus rehearsals. Rhode Island is where my affections are contained, it has a special place in my heart.

Above: Santana doing a pop-up performance at a local market

TW: What was childhood in the DR like?

SS: In the Dominican Republic, I lived with my mom and my sister. We moved around a lot because my mom was a teacher and every year she went to teach at a new school, which also meant we had to switch schools. It sucked to move around so much back then, but it taught us to be comfortable with change.

TW: How old were you when you came to the USA? How was the adjustment?

SS: We moved to the Bronx the Summer I turned 14. It was a time of discoveries, learning a new language, getting on the subway for the first time, and listening to Metallica! I always thought the United States was like the movies, I was thinking Times Square and the Empire State. It was more like bodegas and Spanglish, Puerto Rican flags everywhere! We were embraced by a Latin American community of hard working people, my mom included, who came to this country to do their best, and they did, and they did it while listening to loud salsa and merengue.

TW: The Bronx and Washington Heights are major hubs for Dominican Americans, yeah? What inspired the move?

SS: You remember right, Washington Heights (Manhattan) is a hub for Dominican Americans, and where my mom had her business, a botánica, for 30 years. I lived there my last years in NY; before that I lived in the Bronx. Mine is the classic immigrant story. Mom lost her job in DR, came to the US for a better life, brought us here. The end. Of course, this omits the constitutions of a “better life” because that is always under construction, especially as we incorporate new understandings and experiences.

Above: Goya and gold. Santana in Providence. Photo by Jenny Polanco.

TW: You seemed to be enthusiastic about Metallica...

SS: I absolutely love Metallica. I just went to see them last month at Gillette; took my girls and husband with me. It was a family affair. Metallica was my first live concert (in English) in the United States. I worked a whole weekend—doing inventory at a pharmacy in the Bronx—to pay for my ticket. Faith No More and Guns n Roses were also playing that night. Giant Stadium, New Jersey, I think it was 1992. Metal was a huge part of my teenage years. It allowed me to release some of the frustration I felt about moving to a new place. I bonded with people in my high school over music, which really allowed me to practice my English. I could scream the words and nobody would know if I was pronouncing it right or not. It was great! Highly recommended for anyone looking to learn English!

TW: Metal knows no borders! Related to language learning, we’re curious about your international travels and projects. What stands out?

SS: I went to Italy a while back where I learned I can eat all day and walk more than I thought possible. I also went on a creative trip to Chile, where I met brilliant women, many who were artists. Together with artists Ela Alpi and Shey Rivera Rios, we created a performance called Próceres and intervened monuments in the city of Santiago to address the lack of representation of women in historical monuments that are housed in public spaces. It was a meaningful action to all of us, as we tried to visualize the contributions of women in our society. It's not that men haven’t done things worth celebrating, it's that in the process of honoring those achievements, we forget the contributions of other people. But don't worry, we are here to remind you! From that experience, I learned from the wisdom of so many women, young and old. I learned to also value the wisdom that I carry. It's important to honor both.

TW: Before international residencies and being a published poet...can you think back to any early lessons learned? Like when you were coming into your own.

SS: I was so nervous during my first job interview that I mispronounced my own name. When the lady introduced herself, I was like: "Hi, my name is Sushi Santana." We just couldn't stop laughing, I still got the job, but I was mortified. I learned the importance of not taking yourself too seriously!

TW: Your work with the Creative Community Health Worker Fellowship...where do the arts and public health intersect?

SS: Artists are always contributing to public health, art is a healing practice, I’m intentional about engaging people in the creative process because I know from my own experience that it makes you feel better. It works. I’m interested in a culture that allows people to feel, communicate emotions, embrace their own creativity, and art does all of that.

Above: Documentation of an intervention on Broad Street. Video still by Cormac Crump.

TW: We read somewhere this kind of runs in your family?

SS: My mom has a spiritual healing practice; she had a show on cable (NY) about ancestral wisdom. The concept of healing through ritual, in my case, the ritual of writing and performance is a very comfortable place. I grew up around that. My paternal grandfather, Anselmo, was a medicine man. He was love personified; his presence was healing to everyone around him. He taught us the value of love, the importance of feeling loved. I think people who participate in the creative process are engaging in that type of kindness, even if for a brief moment, you are using the best of you to create something. I work to hold that space because it creates a healthier community, it’s public health.

TW: Going back...you mentioned the artist Ela Alpi and for a second we thought you said El Alfa. Quite different but, here’s another music question. Was/is dembow a big thing for you? What were you listening to as a teen back in the DR?

SS: Dembow as we know it now, wasn’t really big when I was a teenager in DR. What was popular was El General, a Panamanian artist who started a whole movement that eventually progressed into everything that is known now in the realm of Dembow and reggaeton. Obviously, Jamaican Dancehall music and reggae influenced the work of El General, but he was one of the first to do it in Spanish.

I went back to live in DR when I turned seventeen until I was twenty. My influences came from my sister who was really into Rock en Español and I listened to whatever she was playing. I think that first contact opened the doors to other bands and I eventually started listening to Spanish rock stations in DR who also played songs in English. She also loved Bob Marley and we used to listen to him all the time. We partied all the time, I don’t ever remember anyone checking my ID, we used to go bars and clubs with a bunch of friends. It was fun.

TW: Do you play or sing yourself?

SS: I'm interested in music, all different genres, languages. Live music always energizes me, it makes me want to create and explore. I don't play any instruments or sing, but I'm inspired by the experience of live music, theater, movies, etc. I love going to fall festivals, it's my favorite time of year, nature is so magnificent, fall landscapes inform my practice in many subtle ways.

TW: Scrolling through your blog now…there’s documentation of a few events described as being Fluxus-based. What’s your relationship to the movement?

SS: I love that it [Fluxus] is all about process; it doesn't have to be the totality of anything. It allows for a glimpse which is very much what we get in any given interaction.

Above: Outside Gillette Stadium, ready for metal.

TW: We’re close to wrapping up here...before we go, what are a few books everyone should read?

SS: La loca de la casa, by Rosa Montero and Dominicanish by Josefina Báez

TW: Let’s end with this: What are you doing tomorrow?

SS: I'm currently doing a poetry tour of small businesses in Providence. I've stopped at bodegas, supermarkets, and barbershops on Broad Street. Pop-up style. No announced days, I just go and walk in somewhere. This is ongoing work...

*

You can follow Sussy on instagram at @lapoetera, and via her website.

Reconditioning Fitness, with Muscle Brunch